How the rich stole football and the impact on working class fans

The Gentrification of Modern-Day Football in the UK and Ireland and Its Impact on Working-Class Violence and hooliganism

In the UK and Ireland, football has traditionally been seen as the sport of the working class. Clubs were often closely tied to their local communities, serving as outlets for working-class pride and identity. However, as football has become increasingly commercialized and globalized, many aspects of the game have become less accessible to its traditional fan base. This shift has had significant effects on football culture, including a decline in the violence historically associated with hooliganism.

1.Commercialization of the Game

The Premier League and Sky Sports: In 1992, the formation of the Premier League and its lucrative broadcasting deal with Sky Sports transformed football in England. Clubs like Manchester United and Liverpool became global brands, and the game began to cater more to middle-class audiences. The financial boost enabled clubs to buy top talent but also led to increased ticket prices, pushing out many traditional working-class supporters.

Celtic and Rangers: In Scotland, the Old Firm rivalry between Celtic and Rangers used to be deeply embedded in local, working-class communities, with strong sectarian undertones. However, the commercialization of the game has diluted some of that edge. While sectarianism hasn’t disappeared, these clubs now attract fans from beyond Glasgow, diluting the once-intense local atmosphere.

Irish Clubs:

Clubs like Shamrock Rovers in Dublin and Linfield in Belfast are experiencing the effects of commercialization, though to a lesser degree than the big English clubs. The influence of globalized football, however, has led to local Irish fans increasingly supporting Premier League teams over their local clubs, leading to a disconnection between football and its community roots.

2. Middle-Class Influence and Stadium Culture

Arsenal’s Move to the Emirates: When Arsenal moved from Highbury to the Emirates Stadium in 2006, it was a clear symbol of football’s shift from a working-class pastime to a middle-class experience. The Emirates offers premium seating, corporate boxes, and higher ticket prices, attracting a wealthier crowd. This shift has led to a quieter, more sanitized atmosphere in the stands compared to the more raucous environment at Highbury.

Tottenham Hotspur: Tottenham’s new stadium, opened in 2019, is another example of the game’s growing middle-class appeal. It offers luxury experiences like fine dining, corporate hospitality, and even an in-stadium microbrewery. This modernized fan experience contrasts sharply with the club’s traditional working-class roots in North London.

All-seater Stadiums: After the Hillsborough disaster in 1989, which led to the deaths of 96 Liverpool fans, the Taylor Report recommended that all football stadiums in the UK become all-seater venues. This measure greatly improved safety, but it also changed the atmosphere. Standing terraces, where working-class fans gathered, often fuelled by cheap tickets, were replaced by seats, which, combined with higher prices, reduced the accessibility and intensity of match-day support.

3. The Decline of Hooliganism

Policing and Surveillance: The hooliganism that plagued English football in the 1970s and 1980s, particularly in clubs like West Ham United (the “Inter City Firm”) and Millwall (whose fans had a fierce reputation), has dramatically decreased. This is largely due to the increase in policing, surveillance, and penalties for violent behaviour. The creation of all-seater stadiums, CCTV cameras, and increased stewarding has made it harder for hooligans to engage in the violent confrontations that were once common.

Chelsea Headhunters: The notorious Chelsea Headhunters hooligan firm was active during the 1980s, engaging in violent clashes with rival supporters. With the bourgeoisification of football, particularly through Roman Abramovich’s takeover in 2003 and Chelsea’s rise as a global powerhouse, the club has distanced itself from that violent past. However, remnants of hooliganism still exist, though more in the form of organized fights away from the stadium.

Leeds United: Once infamous for their hooligan element, Leeds United has also seen a dramatic reduction in violence. The club’s rise back to the Premier League after years in the lower divisions coincided with an effort to rebrand and modernize, attracting more middle-class supporters. This has diluted the working-class intensity and the hooliganism that once characterized the club’s fan base.

4. Economic Alienation and Working-Class Displacement

Ticket Prices and Accessibility: Clubs like Manchester City have priced out many of their traditional working-class fans. The Abu Dhabi ownership transformed City into a footballing powerhouse, attracting global support, but this came at the cost of alienating local fans. Tickets for big matches, particularly in the Champions League, are often unaffordable for many working-class Mancunians.

Celtic FC: In Glasgow, Celtic FC, traditionally seen as a working-class club with strong ties to the Irish community, has also faced criticism for rising ticket prices. Many lifelong supporters from working-class neighbourhoods have been forced to give up season tickets, feeling that the club is more interested in catering to middle-class fans and tourists who attend the occasional match rather than the local community that has supported the club for generations.

Irish Football: In the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, clubs like Bohemian FC in Dublin or Glentoran in Belfast struggle to keep ticket prices low and fan engagement strong. However, the dominance of Premier League football on Irish TV means many working-class fans prefer to watch English clubs rather than support local teams. This has resulted in declining match-day attendance for Irish clubs, further disconnecting local communities from their football teams.

5. Changing Fan Culture and Violence

Sanitized Stadium Atmosphere: The middle-class gentrification of football has made stadiums safer but has also changed the nature of fan engagement. The days when the crowd acted as a “12th man” for clubs like Liverpool at Anfield or Newcastle Unitedat St. James’ Park are increasingly rare in the biggest matches, as more affluent fans fill the seats. This shift has reduced the tribalism that once fueled violence, but it has also led to a more corporate and passive match-day experience.

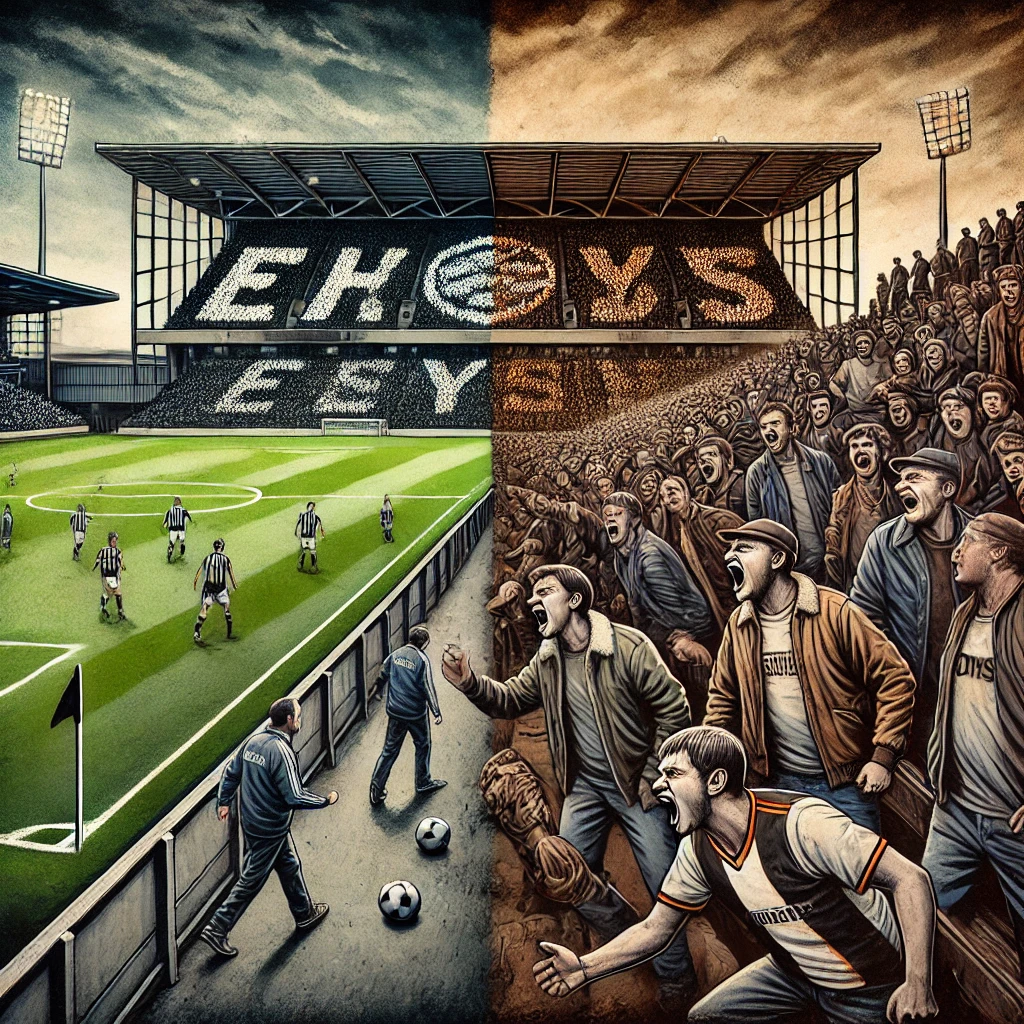

The Rise of Ultras: In some places, such as Celtic and Shamrock Rovers, ultra groups have emerged as a response to the bourgeoisification of football. These groups try to keep the working-class, anti-establishment spirit alive through choreographed chants, displays, and community activism. However, some ultra groups also engage in confrontational behaviour, though not at the levels seen during the height of 1980s hooliganism.

Violence Moving Away from Stadiums: While violence inside stadiums has decreased, clashes between rival fans still happen, but they tend to occur away from the highly-policed environments of the grounds. For example, in recent years, clashes between West Ham and Millwall fans have been more likely to happen in pubs or streets, away from the controlled atmosphere of the stadiums.

Summary

The gentrification of football in the UK and Ireland has profoundly altered the game’s landscape, particularly for working-class fans. Rising ticket prices, commercialized stadiums, and the global marketing of clubs have made football less accessible to its traditional supporters. While this shift has significantly reduced the violence that once plagued the game, it has also displaced working-class fans, leading to a loss of identity and community connection with their local clubs. Football may be safer and more family-friendly today, but it has also lost some of the raw passion and local pride that made it the heart of working-class culture in the UK and Ireland..